Interview: Christopher Campbell, Consulting Engineers South Africa

FreeThe CEO details the issues plaguing the South African construction sector.

As an optimist, Engineer Christopher Campbell is bullish on the future of South Africa’s currently ailing infrastructure sector.

“To coin the phrase often cited by our minister of public works and infrastructure [Dean Macpherson], we should be turning South Africa into one big construction site, especially since it is viewed by most as the gateway to the African economy,” says Campbell, who is the CEO of Consulting Engineers South Africa (CESA), a voluntary association of consulting engineering firms established in 1952.

The CEO has a bevy of designations, including being an executive council member of South Africa’s Construction Sector Charter Council, vice-president and chair of the Committee on Engineering Capacity Building of the World Federation of Engineering Organisations (WFEO) as well as chair of the Directors and Secretaries Advisory Council (DNSAC) of the International Federation of Consulting Engineers (FIDIC). Consequently, he is well aware of the potential of South Africa’s construction industry as well as the challenges it needs to surmount.

“South Africa, along with other major economies on the African continent, is an integral element in the overall growth of our continent and cannot therefore afford to continue on the trajectory [on which] it currently finds itself,” says Campbell.

On the issues dragging the country’s construction sector down, he says there are many factors hampering “what was once a world-class provider of construction services locally and globally”.

“Many [South African contractors] have been forced into almost non-existence [due to] large contractual liabilities in overseas markets, diminishing local markets and significantly decreased investment in gross fixed capital formation in South Africa – [this has] reduced from an average of Rand 350 billion [US$19.8 billion] in 2005 to Rand 220 billion in 2024, an almost 40% reduction (notably annualised against 2015 prices). [But] in fact, the investment should have been in the opposite direction to [tackle the country’s] aging, under-maintained and under-capacity infrastructure to service a growing population of over 60 million citizens and immigrants from other parts of the continent.

“The fact the South African economy has not grown beyond 1% over several years, owing to political and policy uncertainty as well as corruption, has not helped encourage large-scale private sector and international investment. The biggest challenges at the moment would be that of addressing the impact of global criminal syndicates operating in South Africa, [the] adversarial global geopolitical climate, and [the absence of] a stable political [environment].

“Coalition governments are a new phenomenon and more maturity will be required for political parties in such alliances to be more focused on service delivery, infrastructure maintenance and development at local government levels as opposed to the partisan influences, and sometimes even personal interests, of such political actors, which is currently the state of play, especially with a local government election looming in 2026.

“At national government levels, too, despite the [formation] of the current coalition government as a Government of National Unity (GNU) … much has to be learnt from other countries on attaining alignment between parties in such arrangements, which will serve the national interest first. Policy uncertainty and legislative misalignment discourages investment both locally and internationally.

“Despite the huge opportunities and the demand for functional and modern infrastructure, the South African fiscus alone will not be able to fund the many backlogs currently being experienced,” says Campbell.

On the skills shortage and aggressive fee discounting plaguing the construction and engineering industry in South Africa, Campbell notes that “engineering skills in the civil, mechanical and electrical fields are among the 10 scarcest skills in South Africa, according to figures published by our own Ministry of Labour and Employment”.

“In comparison with other developed countries, South Africa has about 1 engineer per 3,000 people, versus developed countries, which boast 1 engineer for every 200 people, according to earlier studies and compared to recent figures,” he says.

“The shortage is, to a large extent, within local government departments and municipalities as well as in various other spheres of government. This means public infrastructure upgrades and maintenance lack sufficient management capacity, which is exacerbated by the onerous bidding processes that precede such projects.

“[Due to] insufficient opportunities, many younger engineers are migrating to other countries where they find more secure employment and ongoing developments [that match] their expertise. Additionally, there is also an aging workforce of seasoned engineering practitioners, some still active well into their 70s, while the cadre that should have been in a position to have been mentored by these aging practitioners are not as large in number as what is required.

“Additionally, the lack of appreciation for the value that engineering practitioners create for any society negatively impacts the potential remuneration that growing practitioners can command. Sadly, both private and public sector clients treat these professional services as a commodity and, when project bids are finalised, these [services] often come with a requirement for massive discounts, which in turn reduce the fee earnings required for a sustainable consulting engineering industry and the retention of such engineering skills. We often see many engineers joining the financial services sector where their skills are better appreciated and the financial rewards are more attractive.

“South Africa, much like many other countries, has a mixture of engineers, technologists and technicians,” says Campbell. “However, there is a greater tendency for high school graduates to pursue the latter two categories of engineering studies, which limits the number of engineers and creates an imbalance between the various categories of engineering practitioners we need as a country.”

Source: Dietmar Rabich | Wikimedia Commons

The CEO also notes that the South African construction industry is susceptible to rampant corruption.

“Not only do we find anomalies related to overpricing and under-delivery (if any delivery at all), the industry is also plagued by extortionists masquerading as business forums, claiming to be representative of communities who are aggrieved about not securing employment and business opportunities when projects are being executed in their localities,” he says.

“The absence of local economic development and implementation fuels the expectation that any temporary construction activity in the immediate neighbourhood should be wholly beneficial to local communities, whereas construction companies who secure these bids are not necessarily domiciled in any one location and subsequently require their core management team and reliable sub-contractors as part of these projects before they source any local sub-contractors (if these are available), to ensure effective and efficient project delivery. Where this balance is created, the projects progress well.

“The opportunism exercised by extortionist groups, known locally as the ‘construction mafia’, generally have no interest in adding value to these projects and are simply rent-seeking. Sadly, our local law enforcement agencies are still battling this scourge and do not seem to be gaining control over such criminality.”

On Africa as a whole, Campbell says: “African governments need to be more focused on changing the narrative that may [stem from] a colonial school of thought, which inculcates a negative self-belief in our ability as Africans to be able to survive and thrive through trade and not aid.

“We have the human capital, especially our younger generation, we have the mineral resources and, by now, have certainly regained the intellectual prowess that was likely decimated centuries ago, when places such as Timbuktu, Mali, in the 15th and 16th centuries were recognised as centres of trade and learning. There are many world-class educational institutions around the continent and many African students often tend to obtain degrees in other countries as well.

“What we need is the eradication of corruption; … we need stable, well-managed governments developing and implementing good policy and providing political certainty. We need these attributes to instill confidence in external investment, which, in turn, should be focused on infrastructure, both economic and social, so that economies can grow and unemployment can be significantly reduced, with [fewer] people falling victim to poverty.

“It is unfortunate that many of our African leaders do well initially and grow investment through infrastructure development and then appear to undo the good they have done by remaining in office when they no longer have the initial drive and energy to continue what they had started. Good legacies unfortunately then become undone.”

The CEO opines that localisation should not be an option, “it should be a given as it is the only way in which we are going to afford local engineering practitioners the appropriate exposure and experience to drive such projects in the future”.

“International expertise is always welcome,” says Campbell. “However, we need to be developing the capacity locally so that we have local construction industries that are able to deliver on future projects as well as support governments that are the owners and custodian of such infrastructure and that are responsible for the lifecycle management of such infrastructure.

“Designs, material and technology choices must be appropriate to local conditions so there are no inherent challenges in obtaining compatible repair and maintenance components. This is especially true for infrastructure of a mechanical and electrical type. However, this could also apply to the difficulty in obtaining replacement components for water distribution systems, where sizes of pipes and components might have been according to imperial measurement systems in the past but now are only available in metric measurement systems.

“Procurement philosophy should be part of the turnkey approach so that local infrastructure [is developed] with long-term effective and efficient asset ownership in mind.”

With South Africa said to be the most industrialised, technologically advanced and diversified economy in Africa, Campbell says the country must act now to reverse its misfortunes.

“Infrastructure development in South Africa has always been viewed as an example of what all infrastructure developments on our continent should resemble,” he says.

“South Africa needs to turn the tide on all of its failing infrastructure areas, so that it does not resemble the state of many of our neighbouring countries, following their own liberation struggles in a post-colonial era.”

Top photo: Engineer Christopher Campbell (Source: Facebook)

Discover

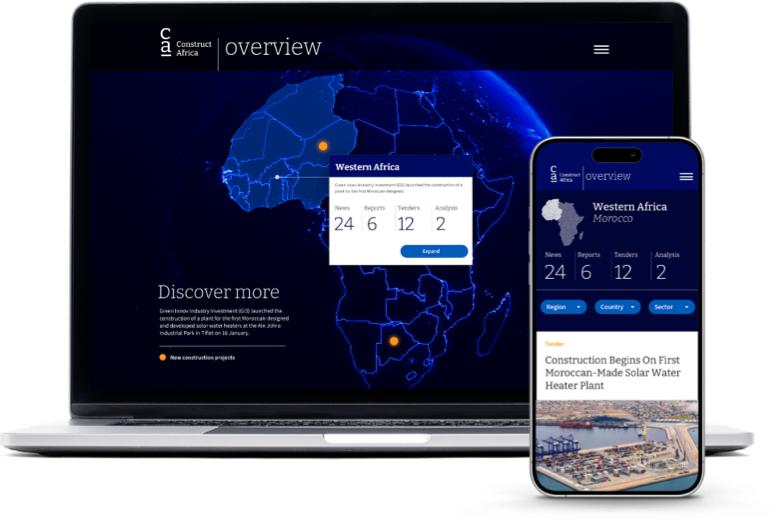

myConstructAfrica

Your one-stop-shop for information and actionable intelligence on the construction and infrastructure pipeline in African countries

- News, analysis and commentary to keep up-to-date with the construction landscape in Africa.

- Industry Reports providing strategic competitive intelligence on construction markets in African countries for analysts and decision-makers.

- Pipeline Platform tracking construction and infrastructure project opportunities across Africa from conception to completion.

- Access to contact details of developers, contractors, and consultants on construction projects in Africa.

- News and analysis on construction in Africa.

- Industry Reports on construction markets in African countries.

- Pipeline platform tracking construction and infrastructure projects in Africa.

- Access to contact details on construction projects in Africa.